Journal Club: Programmable synthetic biocondensates for cellular control

Today, I finally did my first journal club after joining my laboratory in Tohoku University. My research is about biomolecular condensates, so when I first r...

Today, I finally did my first journal club after joining my laboratory in Tohoku University. My research is about biomolecular condensates, so when I first read the title of the article, I thought it would be interesting to cover. The article can be found here https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-022-01252-8.

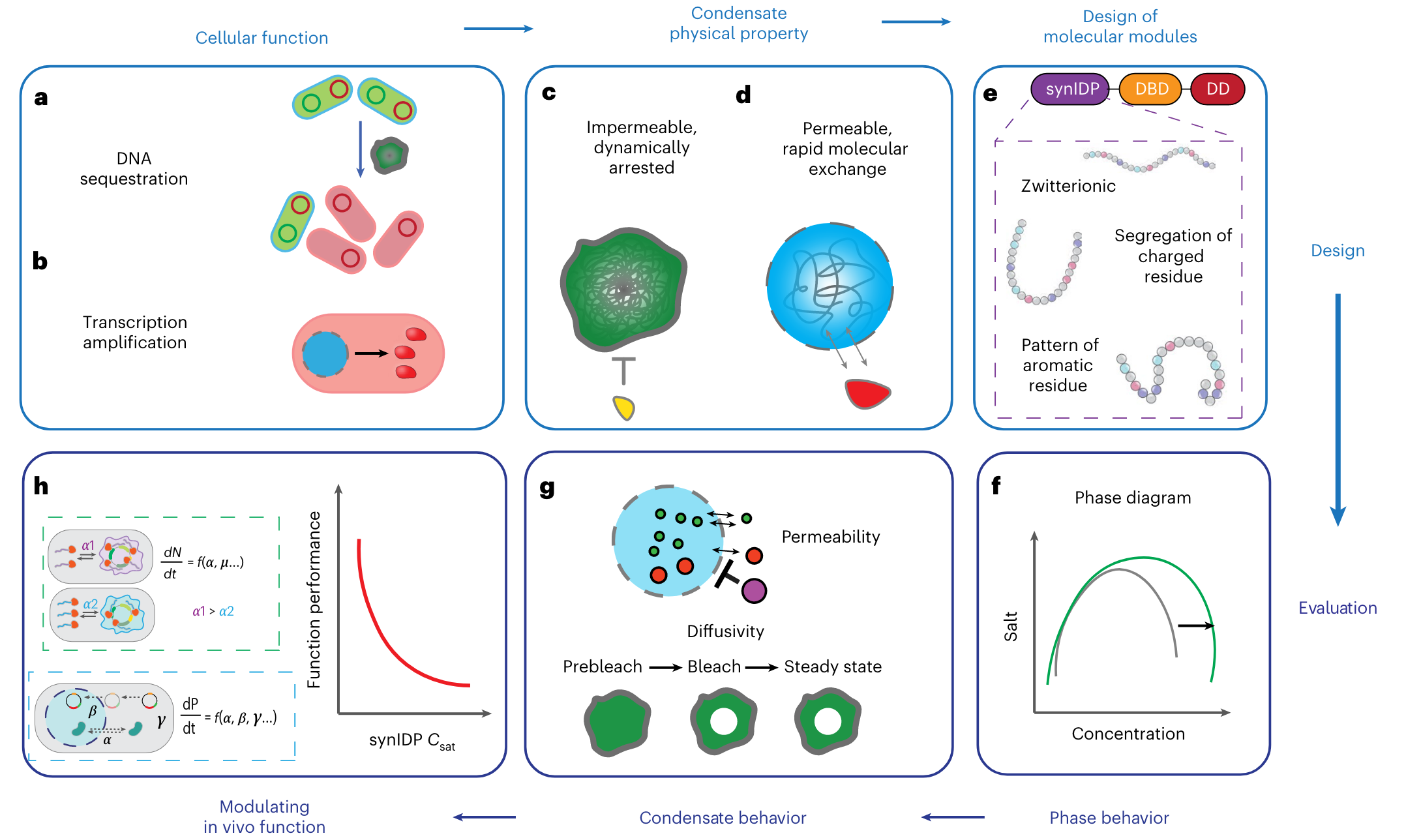

Biomolecular condensates, such as P granules and stress granules, play a critical role in the regulation of cell behaviors. The formation of condensates can be driven by phase separation coupled to percolation (PSCP) of intrinsically disordered protein (IDPs). Condensates can selectively enrich or exclude biomolecules, thereby enabling dynamic control over cellular processes.

Synthetic condensates built by naturally occurring IDPs fused with functional domains have been used to control cell proliferation, reassign codons of selected mRNAs, and control metabolic flow.

Here, the authors demonstrate engineering of functional biomoecular condensates by leveraging the rules that have emerged from studies that have uncovered the driving forces for PSCP. They use these rules to construct fusions of synIDPs and functional domains to modulate the formation and physical properties of condensates and then perform condensate-mediated cellular functions in bacteria and mammalian cells.

The authors selected a class of zwitterionic synIDPs, relisin-like polypeptides (RLP) that are inspired by Drosophila melanogaster Rec-1 resilin protein. The RLPs provide homotypic interactions that drive condensate formation. Each RLP consists of a repeating octapeptide, and the RLP with the GRGDSPYS repeat unit is designated as the wild type.

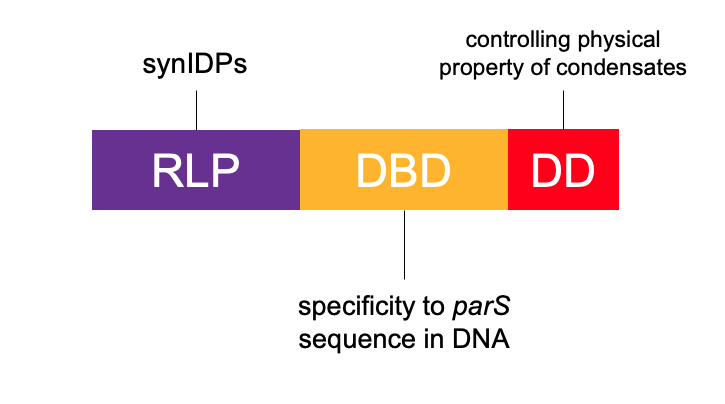

They are using a DNA-binding protein, ParB from Caulobacter vibrioides. ParB interacts with parS sequence to promote chromosome segregation and is orthogonal to existing DNA regulation machinery in Eschericia coli, which does not contain a genomic ParB-parS system. They fused an N-terminal deficient ParB (dParB) containing a helix-turn-helix DNA-binding domain (DBD) and a C-terminal dimerization domain (DD) to RLPs to create RLP-DBD and RLP-DBD-DD fusions. The DBD can interact with specific parS sequences in DNA and thus recruit a target plasmid. Interactions through the DD can increase the valence of cohesive motifs (stickers), that enhance the driving forces for PSCP through homotypic interactions.

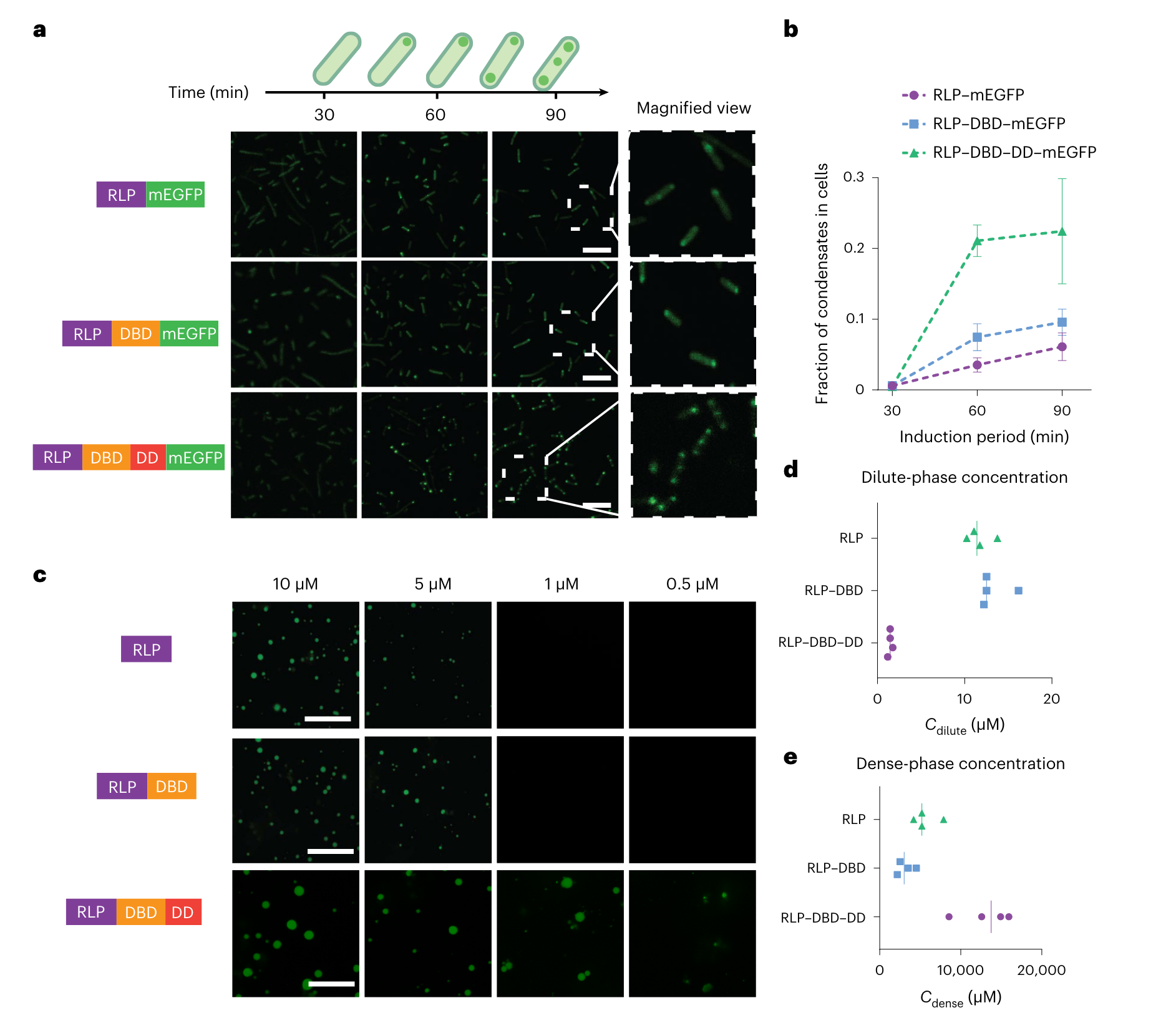

The authors fused monomeric green fluorescent protein (mEGFP) to the C termini of the constructs and the expressed protein in cells formed distinct condensates (Fig. 2a). The area fraction of condensate per cell increased in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 2b), indicating that the condensate formation is concentration dependent or in another word; the condensate grows larger as a result of proteins coming together as time goes. RLPWT showed the fastest condensate formation and generated the largest fraction of condensates per cell. They then quantified the contribution of each domain in the synIDP fusions to phase separation using a sedimentation assay to measure the dilute- and dense-phase separation (Cdilute and Cdense) (Fig. 3c). Comparing the results of RLPWT, RLPWT-DBD produced slight difference (Fig 3.d,e). By contrast, the RLPWT-DBD-DD showed a lowered Cdilute and an increased Cdense. The changes in both parameters were an order of magnitude, suggesting that the DD substantially alters the phase diagram of the RLP (presumably due to the increase in the cohesive interaction).

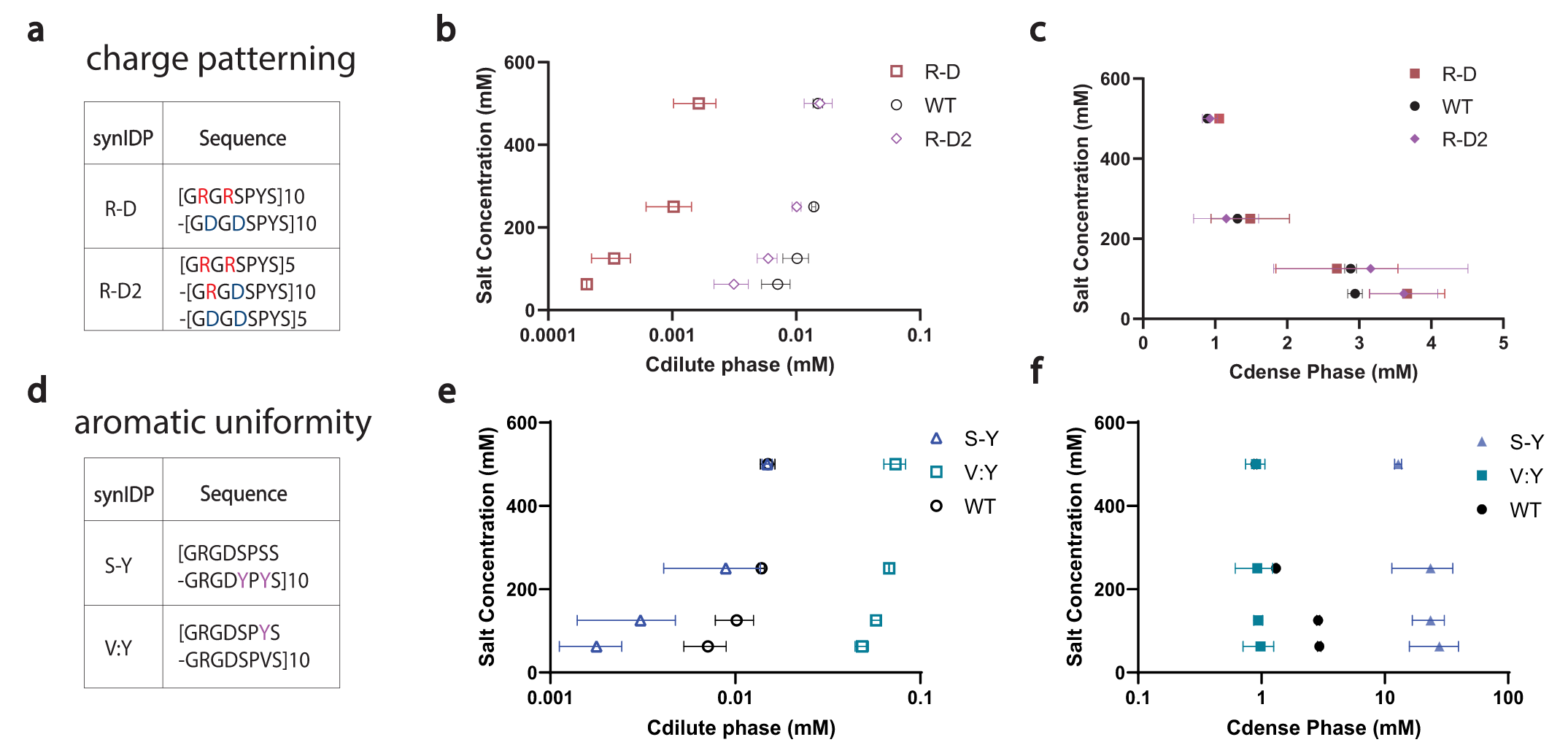

Then, the authors sought to tune the physical properties and the phase behavior of condensates by changing the distribution of charged residues and aromatic residues in the synIDP sequence to create a series of synIDPs. First, the clustering of aromatic residues should increase the interaction between aromatic residues, making each cluster a ‘super sticker’, and should decrease the segmental mobility of the synIDPs within the condensate. Second, the segregation of oppositely charged residues should enhance complementary interactions and thus reduce the saturation concentration for condensate formation.

Today, I finally did my first journal club after joining my laboratory in Tohoku University. My research is about biomolecular condensates, so when I first r...